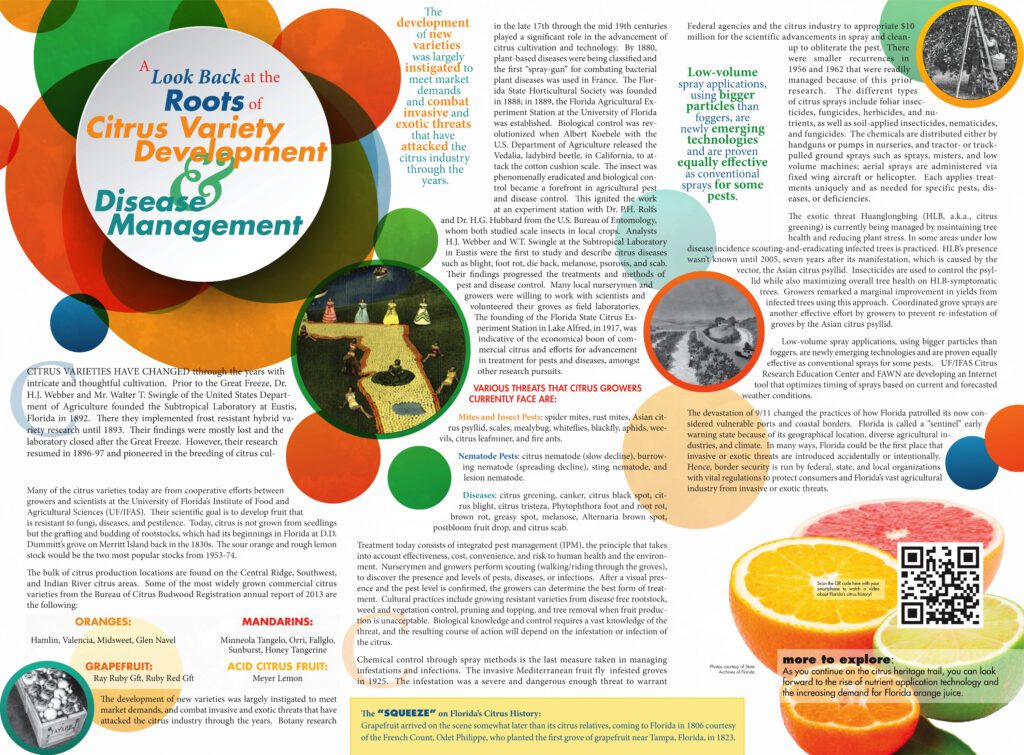

A Look Back at the Roots of Citrus Variety Development and Disease Management

Citrus varieties have changed through the years with intricate and thoughtful cultivation. Prior to the Great Freeze, Dr. H.J. Webber and Mr. Walter T. Swingle of the United States Department of Agriculture founded the Subtropical Laboratory at Eustis, Florida in 1892. There they implemented frost resistant hybrid variety research until 1893. Their findings were mostly lost and the laboratory closed after the Great Freeze. However, their research resumed in 1896-97 and pioneered in the breeding of citrus cultivars.[emember_protected custom_msg=”Click here and register now to read the rest of the article!”]

Many of the citrus varieties today are from cooperative efforts between growers and scientists at the University of Florida’s Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS). Their scientific goal is to develop fruit that is resistant to fungi, diseases, and pestilence. Today, citrus is not grown from seedlings but the grafting and budding of rootstocks, which had its beginnings in Florida at D.D. Dummitt’s grove on Merritt Island back in the 1830s. The sour orange and rough lemon stock would be the two most popular stocks from 1953-74.

The bulk of citrus production locations are found on the Central Ridge, Southwest, and Indian River citrus areas. Some of the most widely grown commercial citrus varieties from the Bureau of Citrus Budwood Registration annual report of 2013 are the following:

| Oranges: Hamlin, Valencia, Midsweet, Glen Navel |

Mandarins: Minneola Tangelo, Orri |

| Grapefruit: Ray Ruby Gft, Ruby Red Gft |

Acid citrus fruit: Meyer Lemon |

The development of new varieties was largely instigated to meet market demands, and combat invasive and exotic threats that have attacked the citrus industry through the years. Botany research in the late 17th through the mid 19th centuries played a significant role in the advancement of citrus cultivation and technology. By 1880, plant-based diseases were being classified and the first “spray-gun” for combating bacterial plant diseases was used in France. The Florida State Horticultural Society was founded in 1888; in 1889, the Florida Agricultural Experiment Station at the University of Florida was established. Biological control was revolutionized when Albert Koebele with the U.S. Department of Agriculture released the Vedalia, ladybird beetle, in California, to attack the cotton cushion scale. The insect was phenomenally eradicated and biological control became a forefront in agricultural pest and disease control. This ignited the work at an experiment station with Dr. P.H. Rolfs and Dr. H.G. Hubbard from the U.S. Bureau of Entomology, whom both studied scale insects in local crops. Analysts H.J. Webber and W.T. Swingle at the Subtropical Laboratory in Eustis were the first to study and describe citrus diseases such as blight, foot rot, die back, melanose, psorosis, and scab. Their findings progressed the treatments and methods of pest and disease control. Many local nurserymen and growers were willing to work with scientists and volunteered their groves as field laboratories. The founding of the Florida State Citrus Experiment Station in Lake Alfred, in 1917, was indicative of the economical boon of commercial citrus and efforts for advancement in treatment for pests and diseases, amongst other research pursuits.

Various threats that citrus growers currently face are:

Mites and Insect Pests: spider mites, rust mites, Asian citrus psyllid, scales, mealybug, whiteflies, blackfly, aphids, weevils, citrus leafminer, and fire ants.

Nematode Pests: citrus nematode (slow decline), burrowing nematode (spreading decline), sting nematode, and lesion nematode.

Diseases: citrus greening, canker, citrus black spot, citrus blight, citrus tristeza, Phytophthora foot and root rot, brown rot, greasy spot, melanose, Alternaria brown spot, postbloom fruit drop, and citrus scab.

Treatment today consists of integrated pest management (IPM), the principle that takes into account effectiveness, cost, convenience, and risk to human health and the environment. Nurserymen and growers perform scouting (walking/riding through the groves), to discover the presence and levels of pests, diseases, or infections. After a visual presence and the pest level is confirmed, the growers can determine the best form of treatment. Cultural practices include growing resistant varieties from disease free rootstock, weed and vegetation control, pruning and topping, and tree removal when fruit production is unacceptable. Biological knowledge and control requires a vast knowledge of the threat, and the resulting course of action will depend on the infestation or infection of the citrus.

Chemical control through spray methods is the last measure taken in managing infestations and infections. The invasive Mediterranean fruit fly infested groves in 1925. The infestation was a severe and dangerous enough threat to warrant Federal agencies and the citrus industry to appropriate $10 million for the scientific advancements in spray and cleanup to obliterate the pest. There were smaller recurrences in 1956 and 1962 that were readily managed because of this prior research. The different types of citrus sprays include foliar insecticides, fungicides, herbicides, and nutrients, as well as soil-applied insecticides, nematicides, and fungicides. The chemicals are distributed either by handguns or pumps in nurseries, and tractor- or truck-pulled ground sprays such as sprays, misters, and low volume machines; aerial sprays are administered via fixed wing aircraft or helicopter. Each applies treatments uniquely and as needed for specific pests, diseases, or deficiencies.

The exotic threat Huanglongbing (HLB, a.k.a., citrus greening) is currently being managed by maintaining tree health and reducing plant stress. In some areas under low disease incidence scouting-and-eradicating infected trees is practiced. HLB’s presence wasn’t known until 2005, seven years after its manifestation, which is caused by the vector, the Asian citrus psyllid. Insecticides are used to control the psyllid while also maximizing overall tree health on HLB-symptomatic trees. Growers remarked a marginal improvement in yields from infected trees using this approach. Coordinated grove sprays are another effective effort by growers to prevent re-infestation of groves by the Asian citrus psyllid.

Low-volume spray applications, using bigger particles than foggers, are newly emerging technologies and are proven equally effective as conventional sprays for some pests. UF/IFAS Citrus Research Education Center and FAWN are developing an Internet tool that optimizes timing of sprays based on current and forecasted weather conditions.

The devastation of 9/11 changed the practices of how Florida patrolled its now considered vulnerable ports and coastal borders. Florida is called a “sentinel” early warning state because of its geographical location, diverse agricultural industries, and climate. In many ways, Florida could be the first place that invasive or exotic threats are introduced accidentally or intentionally. Hence, border security is run by federal, state, and local organizations with vital regulations to protect consumers and Florida’s vast agricultural industry from invasive or exotic threats.

Click here to view video content.

| Exhibit 1 | Exhibit 2 | Exhibit 3 | Exhibit 4 | Exhibit 5 |

CREDITS

story by J.P. SMITH

[/emember_protected]