Florida Ag Industry Sees a Rising Trend in African-American Farmers

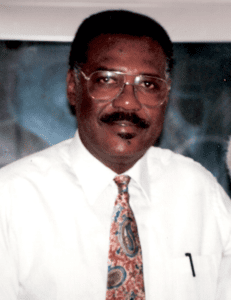

Seventy-nine-year-old Herman Hargrett Sr., a retired ag teacher, is one of the few black farmers in Florida. But their numbers are growing.

Hargrett is making plans to push up his second citrus grove in Bealsville. Though he retired from teaching agriculture, he has no plans to retire from farming. “If you want to die, just go ahead and retire and watch Gunsmoke all day, and see how long you’ll last,” Hargrett quips. Hargrett owns 15 acres and helps caretake another 70 he and his siblings inherited. He grows citrus and truck crops off State Road 60 about a mile and a half west of the Polk-Hillsborough County line. He has about eight acres in citrus left after pushing up one grove because of citrus greening. Before long, he’ll be down to one citrus grove and truck crops. Things haven’t been easy for citrus growers. As a black farmer, he’s in the minority in Florida. “I don’t know of too many more [black farmers] in the area,” he admits. “Sometime I see them by the roadside.”

Yet, the number of farms in Florida with principal operators who were black or African-American rose from 1,068 in 2002 to 1,481 in 2012, according to the latest available U.S. Census of Agriculture. There were a total of 47,740 farms in 2012.

The food movement, at the least, seems to be spurring renewed interest in agriculture among women, both black and white, says Howard Gunn, Jr., president of Florida Black Farmers and Agriculturalists Association in Ocala, which is open to anyone. “Young educated females are really getting into farming and sustainable living,” says Gunn, who holds a bachelor’s degree in Agribusiness from Tuskegee University in Alabama. “They’re really getting more concerned with their health.”

Health-conscious millennials are more interested in growing organic or raising niche crops like blueberries or mushrooms, explains Gunn, who raises cattle and thoroughbred horses in the Ocala area. At one point, black farmers were in serious decline in the United States. According to The Decline of Black Farming in America, a 1982 report of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, the number of black-operated farms had decreased 2.5 times the rate of white-operated farms. “Only 57,271 black-operated farms remained in 1978 compared to approximately 926,000 black-operated farms in 1920,” the report states. “Thus, almost 94 percent of the farms operated by blacks have been lost since 1920, and at the current rate of loss there will be fewer than 10,000 black farmers in the United States at the end of the next decade.” A class action discrimination lawsuit by black farmers against the U.S. Department of Agriculture, known as the Pigford cases, resulted in a $1.25 billion settlement in 2010.

Education has been a boon in helping black farmers combat discrimination and benefit from niche marketing opportunities. “If you don’t know what to ask for, the information is not always willingly given,” Gunn states. “Racism exists.” Still, he prefers to talk about the food revolution or agriculture movement. “We have had some positive change,” he says.

Many of Florida’s Afro-American farmers are concentrated in the north Central or North Florida, with Marion County being a hub. Many raise beef cattle, but others grow squash, cantaloupe, and other fruits and vegetables. “We [the association] thought it was necessary for us to get involved to preserve the few farms that do exist,” Gunn adds. In the Fort Myers area, 26-year-old Matt Griffin works as an assistant farm manager for the Immokalee-based Lipman Produce, growing a variety of crops including tomatoes, citrus, eggplants, bell peppers jalapenos, squash, and green beans. “From a young age, I’ve had a passion for the industry,” he says. “I was in FFA, 4-H, Junior Cattlemen, and some of the other ag organizations.”

He suspects there aren’t more black farmers because not everyone had mentors like he did. But he expects more blacks to embrace agricultural support careers. Farming and ranching are only a small part of the ag industry, he points out. “There’s a ton of other jobs and career paths that you can take in this industry,” he observes.

Like other farmers, black farmers focus on the positives. Hargrett says he has “no particular challenges,” other than trying to get to market first to get good prices. He doesn’t try to get loans. “I avoid problems there. I’m from the old school . . . If I can’t do it out of my pocket, then I don’t fool with it,” he says. “The ag industry here in Florida is a very tight knit community,” Griffin points out. “For the most part, if you share their common interests, and they realize you’re sincere, like minded, I don’t see you really having a problem.”

CREDIT

by CHERYL ROGERS