The Agriculture Way of Life: Guarding Water Quality and Preserving Wildlife

At one time, the Everglades covered nearly 11,000 square miles. Water flowed south from the Kissimmee River into Lake Okeechobee and through the Everglades into Florida Bay. But draining the marshes has cut the Everglades to half the size it was 100 years ago. [emember_protected custom_msg=”Click here and register now to read the rest of the article!”]

Today, it is still home to dozens of threatened and endangered species like the Florida panther, American crocodile, snail kite, and wood stork. Florida has invested more than $1.8 billion to improve water quality, and more than $2.4 billion is dedicated to a state-federal partnership to restore the wetlands.

So, as landowners at the headwaters of the Everglades, Layne and Cary Lightsey take their job as environmental stewards seriously. “We try to do things to make sure the water goes through some filtration,” Layne says. “We try to grow grasses that will pick up those nutrients.”

Layne and his younger brother Cary, partners in Lake Wales-based Lightsey Cattle Company, recognize the importance of being proactive instead of reactive when it comes to water quality. “We’re all just here for a short period of time,” Layne says. “I’ll leave it in somebody else’s hand. I got to make sure I pass that baton effectively.”

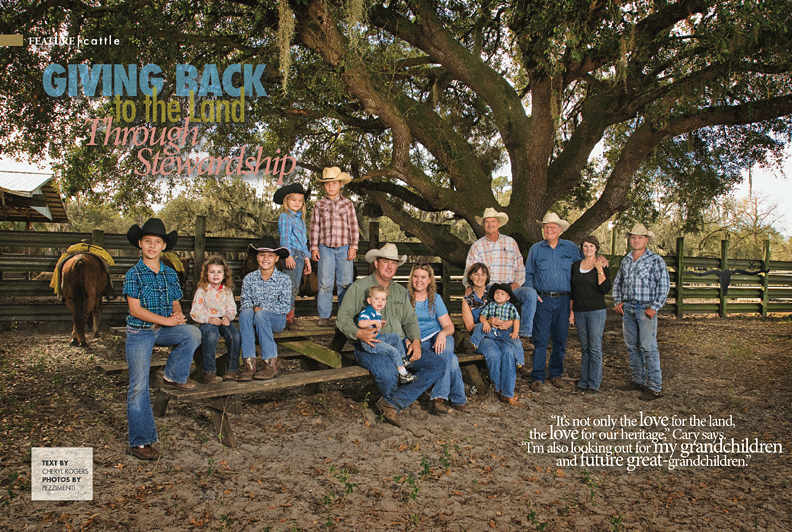

“It’s not only the love for the land, the love for our heritage,” Cary says. “I’m also looking out for my grandchildren and future great-grandchildren.”

The Lightseys have been in Florida and agriculture since 1858, raising cattle, citrus, and, at one time, a dairy. They are one of two Florida ag operations designated as a “Century Farm” by the American Farm Bureau Foundation for Agriculture and its partner, Capreno herbicide (http://www.agricultureslastingheritage.org/profiles/).

“We work with NRCS (the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources and Conservation Service). We try to incorporate best management practices,” Layne says.

For the Lightseys, being good stewards involves planting Bahia grass and millet in cattle crossings to avoid runoff from the ditches. It involves installing flatboard risers on pipe structures to keep water in the ditches long enough for the nutrients to settle, instead of floating into nearby waterways. It means keeping engines and fuel tanks for stationery wells in concrete containment areas to prevent oils and diesel fuels from entering the aquifer. It includes spraying invasive plants like the old world fern that can overtake and kill cypress trees. It means using solar power to run water wells. And it involves prescribed burns on vacant land.

“Animals don’t do well on land that’s not burned every two to three years,” Layne explains. “Also, that encourages your wire grasses.”

It’s a juggling act to make a living and conserve the land, but the Lightseys have handpicked at least 40 percent of their thicker habitats to remain in a natural state.

“I’ve got sandhill cranes in my backyard that will eat out of my hand,” Layne says. “The deer, the turkeys, you want some places where they can hide. … For the eagles, we want to make sure they have plenty of trees to nest in.”

Together, the Lightseys own 22,000 acres and lease 23,000 more in Florida and Georgia. They raise 8,800 mama cows in four Florida counties: Polk, Highlands, Pasco and Osceola. Six ranches are in Polk, including their home base at Tiger Ranch east of Lake Wales.

“I think that cattle are compatible with the wildlife. They both need the wind protection and cold protection,” Cary says. “There is viable food for the cattle in the native land.”

Through easements, they have dedicated the bulk of their land to conservation, protecting it from land developers and preserving it for future generations. “Our goal is to preserve it so we can still make a living,” Cary says. They’ve built into the easements agriculture-friendly property uses and small sections where future generations can live as they work the land. “It’s hard to make a living in the cow business if you don’t live there,” Cary explains. “There’s always work to do.”

In October, the Lightseys earned the County Alliance for Responsible Environmental Stewardship (CARES) Award, a distinction for going above and beyond the requirements of environmental stewardship at its Brahma Island and XL ranches, says Scot Eubanks, CARES coordinator for the Florida Farm Bureau Federation. The federation has partnered with the state’s Department of Agriculture and University of Florida to promote best management practices (BMPs), intended to improve water quality and mitigate environmental impact.

“Pretty much all ag is covered with these programs. It’s separate for each commodity,” says Brian Boman, who coordinates the BMP program from the Indian River Research and Education Center. Landowners voluntarily submit a notice of intent to implement the BMPs, along with a checklist. Then they keep records as they follow through. “This is probably one of the last things on their minds. They’re worried about labor, harvesting, everything else,” Boman says. “It’s certainly an important thing they need to consider.”

The cow/calf industry, which utilizes 10 million acres statewide, became involved in the program a year and a half ago. The citrus industry and other major growers also have enrolled. “There are still growers we haven’t reached with the program yet,” Boman adds. “Most recently, the blueberries growers have jumped on it. We’re working with tropical fruit people now.”

Linda Crane, an environmental specialist for the Florida Department of Agriculture based in the Okeechobee Service Center, assists landowners to apply BMPs in the northern Everglades. “Landowners have two choices. They can work with our department and do the best management program–work with us and let us help them,” continues Crane, “or they can do their own monitoring at their site level at their cost. That’s very expensive.”

Crane understands some are scared to work with regulators. “The last person somebody wants to work with is the government,” she acknowledges, “there’s so many regulations out there.” Of the Lightsey ranches, she says, “they’re just beautiful, perfect mosaics. … You have wetlands, pines, pastureland.”

“Water eventually goes to the Everglades on both sides,” Crane points out. “That’s why it’s very important.”

CREDITS

story by CHERYL ROGERS

photo by PEZZIMENTI