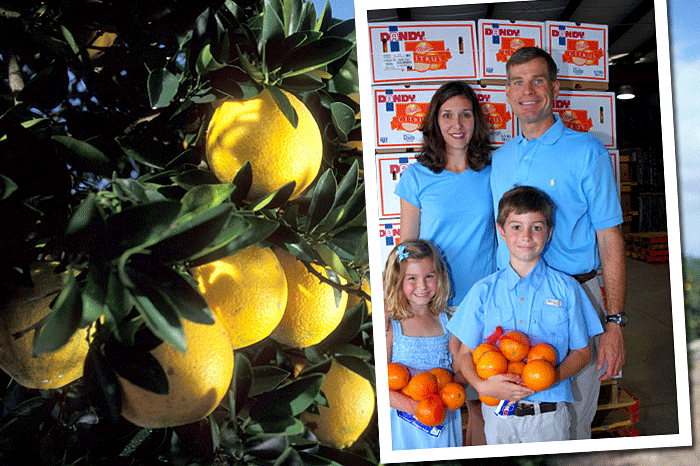

In the photo: Larry Black with wife Jenny and kids Julia and Varn are among many Florida citrus growers who are in it for the long haul.

| Growers making gains against greening |

VIC STORY JR. grew up in the middle of an orange grove his father planted. So, in his 66 years he’s faced a number of challenges – from the tristeza virus killing trees on the sour orange root stock, to canker, nematodes, freezes and hurricanes. But the bacterial disease citrus greening (also known as Huanglongbing or HLB) tops them all.

“This is worse, to the extent that it affects the whole industry,” concedes Story, who has worked in the citrus industry full time since the 1960s. The only thing that it compares to is the low price, below cost production. That will put you out of business faster than anything.”

But Story, president of the Lake Wales-based Story Companies that manages 5,500 acres of citrus, says he and sons Kyle and Matt have made a business decision. “We think we can manage and make a profit.” They are not alone.

Larry Black is actively working on a number of fronts, as general manager of Fort Meade’s Peace River Packing Company, as board member and vice president of the northern area of Lakeland-based Florida Citrus Mutual, and board member of the Citrus Research Development Foundation in Lake Alfred. “Greening is a huge challenge. We’re adapting,” says Black, past president of the Polk County Farm Bureau. “It’s no easy task.”

He notes that the demand for nursery trees is greater than the supply. “Growers in general see a bright future,” he explains. “It’s the biggest challenge this industry has faced, but there is reason to be optimistic.”

Higher prices have helped growers balance their cost of doing business, which may have doubled in the last five years because of greening. “We just wrapped up a successful year for virtually all components of the industry. The growers enjoyed good pricing,” Black says.

Andrew Meadows, communications director for Florida Citrus Mutual, also is positive. “Growers are a resilient bunch and have faced many challenges over the years. But we’ve always found a way to survive and thrive,” he says. “HLB is just the next challenge. We are optimistic the industry’s massive research effort will find short and long-term solutions.”

Polk County has been the biggest producer in Florida’s citrus industry, which has an annual economic impact of some $9 billion. It employs nearly 76,000 people and covers more than 550,000 acres.

June data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture data shows the industry is holding its own. The June Citrus Forecast shows all orange production up less than 1 percent, with 146.2 million boxes. Grapefruit, tangerine and tangelo production are unchanged at 18.8 million, 4.3 million and 1.15 million boxes, respectively.

Looking back to the previous year, a report for the 2010-2011 season published by the Florida Agricultural Statistics Service, estimates that Polk produced 29.8 million or nearly 18 percent of the state’s 165.9 million boxes of citrus. Highlands County – the second largest citrus producer – had 23 million boxes. Polk also had the large number of active commercial acreage in citrus in 2011, at 82,577 of the total 541,328, the report estimates.

Florida supplied 63 percent of U.S. citrus, up 4 percent more than the previous year’s 159.4 million boxes, the 2010-2011 report estimates. All varieties show increases except for grapefruit and late-maturing Honey tangerines, it notes.

The preliminary on-tree value of Florida’s crop was estimated at $1.145 billion, two percent greater than for 2009-2010. “The price per box is higher for non-Valencia oranges, tangelos, and Honey tangerines. The tangelo on-tree value increased 58 percent from last season,” the report notes. “Only the grapefruit on-tree values are lower.”

There’s also more positive news: A reduction of Asian psyllids carrying the dreaded greening bacteria, reduction in abandoned groves, and hope for long-term relief from a gene to breed greening-resistant trees.

Growers have banded to form 38 Citrus Health Management Areas (CHMAs), which have succeeded in reducing the Asian psyllid populations by about 68 percent through pesticide spraying, says Dr. Michael Rogers, associate professor of entomology at the University of Florida’s Citrus Research and Education Center. “It’s early to say how much more” the population can be reduced, he says, although they are seeing a lot of interest in areas where there are a large concentration of smaller groves. “I think we’re going to see significant improvements.” He considers it a band-aid to “keep the industry going until a better solution is developed.”

USDA data confirms abandoned groves are becoming less of a problem. In Polk, the acreage has dropped from 11,830 to 9,749 acres, while statewide totals have fallen from 139,599 to 136,534 acres. The CHMAs, together with tax incentives, are offering positive encouragement to remove or restore abandoned groves.

And there is hope of a solution through dedicated research being conducted by scientists looking for a gene to produce greening-resistant trees. “In the seven years that we’ve had the disease, it’s spread throughout the state … in some groves 100 percent of the trees are infected,” says Dr. Harold Browning, chief operations officer for Citrus Research and Development Foundation. “The final solution, the one that people want to have, would be starting a new orchard or groves with new trees that are resistant to the disease … it doesn’t look like it exists anywhere in the world.”

However, he estimates in as early as a year a gene may be isolated that could be used to breed an assortment of greening-resistant citrus trees. It would be another three to eight years before the trees would become available for planting.

In the meantime, University of Florida Professor of Plant Pathology Bill Dawson says researchers also are exploring how to use the tristeza virus as a way of getting a resistant gene to the plants more quickly. “It will protect trees for a while,” he says. “The idea is that we may be able to use this as a band-aid until resistant trees are available.”

As researchers and growers wrestle with greening, Doug Ackerman is developing new strategies to market citrus. Ackerman, who took over as executive director of the Florida Department of Citrus in January, brings supermarket experience to the task. He is getting back to basics: 1) growing the demand for citrus products so it’s part of their daily lives and 2) protecting the supply. He is working on “new key strategic initiatives” as well as the means to measure success.

They’ve chosen not to rely on celebrity advertising, instead favoring shopping marketing programs and social media, he reports. “I’ve seen how important it is to speak to customers at the point of purchase.”

Using websites like Facebook and Pinterest, the Florida Department of Citrus is promoting delicacies like Tropical Waffles, Florida Smiles Smoothie, Grapefruit French Toast Casserole with Sweet-n-Citrus Salsa, Gluten-Free Orange Soda Bread, and Florida Citrus Fruit Skewers paired with zesty orange dip. “Digital media and social media are very important to us,” Ackerman says. “We’re trying to target our next group of loyal consumers.”

Ackerman says he’s been in a “whirlwind” learning about the industry. “It’s been crazy, but a lot of fun.” He regards the people as the industry’s real strength. “The growers and those responsible, they really step up when they need to,” he observes. “It’s an amazing group of people.”

CREDITS

story by CHERYL ROGERS

family photo by RON O’CONNOR, Farm Credit