by BRAD BUCK, UF/IFAS

Summer brings daily storms in the Sunshine State, and with the rain, you need to control flooding in some neighborhoods. Florida is swimming in 76,000 stormwater ponds.

Designed to control flooding, stormwater ponds are not as effective as natural ponds at removing nitrogen, a pollutant that can go downstream into lakes, rivers and other bodies of water, new University of Florida research shows.

New neighborhoods must use stormwater-control measures to handle any changes in stormwater runoff.

Stormwater ponds are usually installed before houses because you need to have them in place before any potential hydrological or ecological impacts could occur on downstream waters. But sometimes homes and developments are built around naturally occurring ponds.

Despite the prevalence of stormwater ponds, scientists say the internal processes within them are understudied.

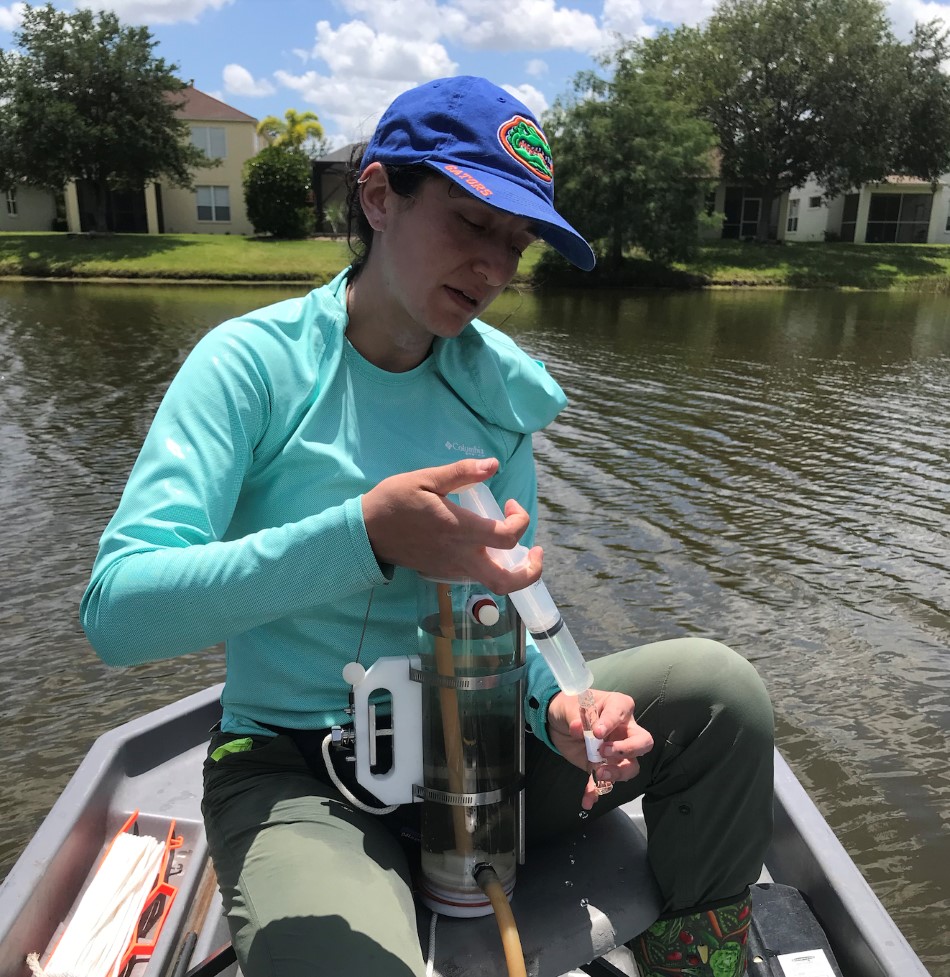

That’s why Audrey Goeckner led the new study. Goeckner will earn her Ph.D. from the UF/IFAS College of Agricultural and Life Sciences this summer.

As part of her dissertation, Goeckner did this research under the supervision of AJ Reisinger, a UF/IFAS assistant professor of soil, water, and ecosystem sciences.

Scientists conducted the study in Melrose (natural ponds) and Bradenton (stormwater ponds). But they said their findings are likely applicable across Florida.

They measured the amount of dinitrogen gas dissolved in ponds. Dinitrogen makes up 80% of the atmosphere, and the amount dissolved in a pond can be used to understand the balance of two competing nitrogen cycling processes: denitrification and nitrogen fixation.

Denitrification is the permanent removal of nitrogen from the system, and it benefits water quality. Nitrogen fixation is an input of nitrogen into the system from the atmosphere, and because it’s a new input of nitrogen, it negatively impacts water quality.

Scientists found that the natural ponds they studied were more likely to remove nitrogen than to produce it by supporting denitrification more than nitrogen fixation. In contrast, stormwater ponds were equally likely to remove or introduce nitrogen by supporting either net denitrification or nitrogen fixation.

“This is important because stormwater ponds are expected to remove nutrients from runoff,” Reisinger says. “But when researchers have compared nitrogen in water coming into stormwater ponds (stormwater runoff) versus going out of stormwater ponds (discharge), stormwater ponds often don’t remove as much nitrogen as we expect.”

The new research supports the concept that stormwater ponds should be recognized as ecosystems that support a range of processes that alter elemental cycles. They’re not just inert bowls of water for stormwater sediments to settle, Goeckner says.

“Stormwater ponds are one of the most commonly used stormwater control measures,” she says. “If water managers are interested in targeting nitrogen removal, this work should prompt them to assess their effectiveness or to consider alternative stormwater control ecosystems.”