Nicole Walker & Bridget Stice May Work Behind the Scenes, but Their Impact Is Front and Center

by REBEKAH PIERCE

This month, Central Florida Ag News is celebrating women in agriculture. Here in Polk County, we’re especially blessed to have such strong female leaders at the UF/IFAS Extension office to thank for their hard work and advocacy — Nicole Walker and Bridget Carlisle Stice.

In addition to countless other pioneering women, these two local extension leaders are leading the charge for equity in agriculture and forging a path for future generations of female farmers and leaders.

Their journeys — each vastly different yet equally inspiring — highlight the diverse paths many of us take enroute to rewarding careers in the agriculture sector.

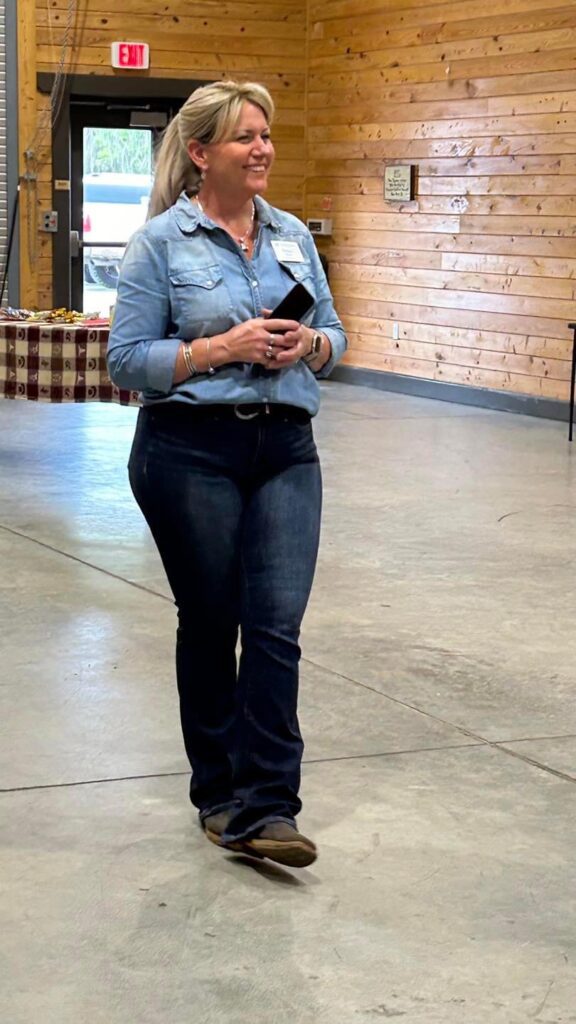

Nicole Walker: English Major to Agriculture Powerhouse

At first glance, Nicole Walker’s resume might seem a little unusual.

“I had no initial interest in agriculture,” she says. “After I graduated from college, with an English degree, I did one year of AmeriCorps service with Public Allies.” It was in that program, in Delaware, where Walker was assigned to a local nonprofit agency where she worked with a 4-H program.

Here, Walker was tasked with providing communications-related support (a nod to the English degree) to the extension and leading two 4-H clubs. By the program’s end — regardless of whether she was writing press releases or working with kids — she was hooked.

Drawn to agriculture and its ability to keep kids from all backgrounds connected, she landed in Polk County at the Extension. The reception was mixed, says Walker, who recalls that some people were skeptical that an English major without much of an agriculture background could be successful in the Extension.

But Walker persisted, driven to show the community how truly invested she was. Her strategy? Attending all the events, big and small, and asking all the right questions.

“I can’t tell you how many horse shows I’ve been to,” she laughs. Her first Polk County Youth Fair was in 2000 and she was amazed. “I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. I wanted to understand.”

Over time, she began to learn. She discovered that showing cows, for example, wasn’t the only point of 4-H. An important piece, yes, but the education that the kids receive in the process and the introduction to the industry was so much more important.

Her efforts to learn about everything paid off, and she now serves as director of the Polk Extension, where she focuses on 4-H and community development. She works closely with families, schools, nonprofit organizations, and agricultural producers to educate them on environmental stewardship, agricultural practices, healthy living, youth development, and more. .

Bridget Carlisle Stice: From Pint-Size

Horse Lover to Livestock Extension Leader

Like Walker, Bridget Carlisle Stice also did not have farming in her DNA, instead growing up in West Palm Beach.

Despite her more coastal upbringing, Stice was drawn to agriculture from a young age, citing an early childhood obsession with horses that persisted long into her adult years.

“Everything I did revolved around horses,” she explains, “from the books I read to saving every penny I earned so that I could spend my days at the horse barns.”

Her parents, who Stice now realizes were “truly smart” to find a way to keep her motivated and out of trouble, encouraged her to go to college to pursue a career that would allow her to continue working with horses.

She just wasn’t sure what kind of career that might be. Although her grandfather had grown up on a horse farm, her parents were still a full generation removed from anything close to agriculture, and her high school didn’t have an ag program.

As a result, Stice pursued a career in the only area that made sense at the time: veterinary medicine. She wound up at the University of Florida in the animal science program. There, she found a special interest in beef cattle production, and — more importantly — she discovered that the list of careers in agriculture goes far beyond veterinary medicine.

Today, Stice is part of an almost all-female team of livestock extension agents that serve southern Florida ranchers. Like Walker, she’s found communication to be key in her role.

“My most valuable and personal achievements come in one-on-one conversations with producers when they mention in passing how something that we discussed helped them in their operation,” she says. My personal and professional values are framed around helping people, and that is what the Extension service is all about.”

Like Walker, Stice found that most of her challenges in the early days of her Extension role came not from being a woman in agriculture, but from being new to the industry.

“But what I lack in family history and physical prowess,” she says, “I try to make up for in my willingness to work hard. When this community sees someone who is willing to work hard, they embrace them with open arms, no matter their gender, family background, nationality, or whatever other challenge one believes to stand in their way.”

According to Stice, the agriculture community continues to seek out and recognize women who are willing to work hard and to offer those leadership opportunities.

“We need to encourage young people, male and female, that hard work is what will set them apart.”

Empowering the Next Generation of Women in Agriculture

Stice believes that the future of the agriculture industry is dependent on the ability to educate people about agriculture.

“Maybe two generations ago, the vast majority of Americans were either directly or semi-directly involved in agriculture. They were aware of where their food came from and how it was produced. But as our country becomes more urbanized, people lose their connection and understanding of agriculture production. They influence legislators, who make decisions that may or may not support the future of agriculture.”

Stice says it’s everyone’s responsibility to share knowledge about agriculture, and it’s her hope that she can help provide the resources necessary to spread that knowledge.

Currently, she’s working on a project in conjunction with the Hendry and Okeechobee County Extensions known as Adopt a Cowboy. It involves a series of educational videos that culminate with giving young students the opportunity to meet the host cowboys and cowgirls, as well as their horses.

“It’s another great and fun way to help educate youth about animal agriculture that involves the local community,” Stice says.

Today, Walker’s efforts are guided by a holistic understanding of the agriculture industry — one that only a person with an insatiable curiosity (like herself) could ever hope to develop.

She says, “I kind of came up on a different side of the agriculture mountain. The piece of agriculture I represent is agricultural literacy. It doesn’t matter that I don’t come from an agricultural background. It doesn’t matter that I’m not a part of that inner circle of producers. I’ve [worked] to understand the challenges of being an ag producer, as well as the wonderful things that come out of it, of being a steward of our land.”

Being able to see the other sides of things, she reflects, is what has made her an advocate for educating the public.

“I see the curiosity, I hear the curiosity…the public needs to know what’s going on in agriculture. They need some knowledge of the importance of agriculture.”

Together, Walker and Stice are working hard to spread the news about what’s going on in the world of agriculture and to drum up support. Though much of the work these two women do is behind the scenes, it certainly has not gone unnoticed.